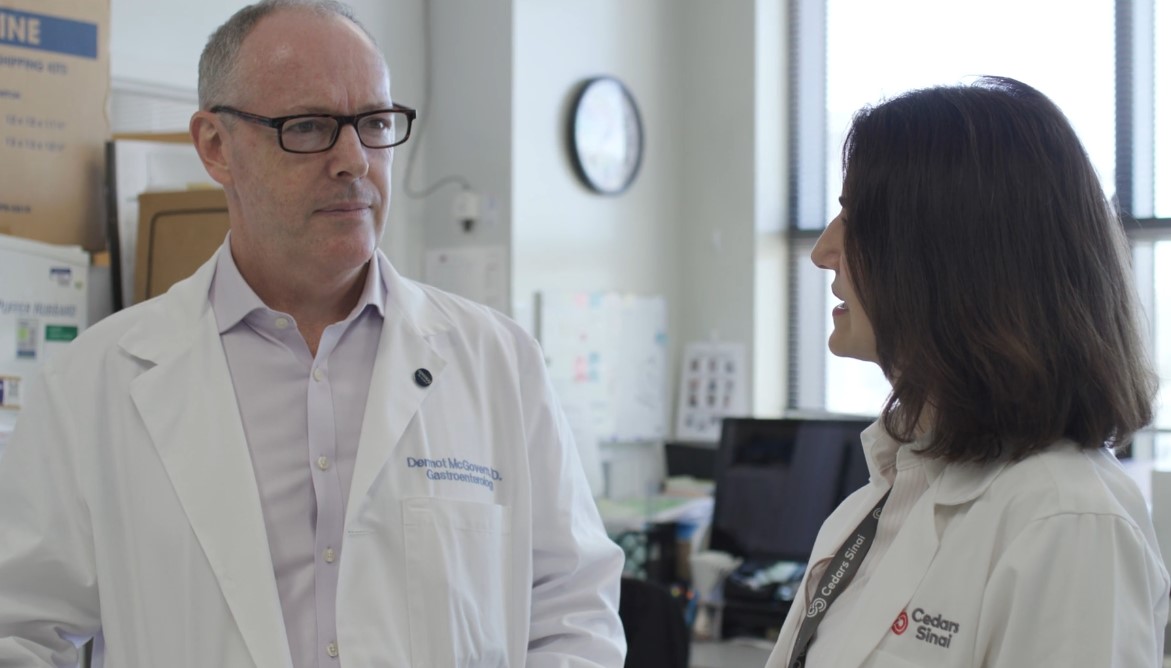

Director, Translational Medicine at the F. Widjaja Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute; Director of the Precision Medicine Initiative; Professor of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences; Joshua L. and Lisa Z. Greer Endowed Chair in IBD Genetics; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, CA

Dr. Dermot McGovern has spent a lifetime fundamentally advancing our understanding of the genetic architecture of IBD as he pursues his mission to deliver personalized medicine to patients. Yet in the soft-spoken and gracious manner his colleagues have come to know, he readily credits others.

“When I was doing my PhD at Oxford, it was just the start of when genetics was beginning to get very interesting in IBD,” said Dr. McGovern. “I had landed in the right place at the right time with a fantastic mentor, one of the giants of IBD in the world, Derek Jewell.”

As you peel back the layers of Dr. McGovern’s journey, one fact becomes evident: making personalized medicine a reality in IBD by advancing genetic research is, indeed, very personal.

Born in Zambia to parents dedicated to public service, Dr. McGovern saw the world and his parents’ role in it — moving from Africa to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and then to the UK, all before finishing high school.

“My parents believed very much in the importance of education and using it to improve society and address its most pressing problems. That was very much ingrained in me and my sister.”

His path to medicine was fueled by that principle, with a love of science, an empathy for suffering, and a desire to connect with and help people, medicine was a natural progression. Dr. McGovern ultimately chose to specialize in IBD because of the breadth of opportunity to make a difference. Early in his journey, it was the simple question of an IBD patient that set him on a path to try to solve one of IBD’s most intractable problems.

Said Dr. McGovern, “I had a formative experience with one patient who asked me ‘How do you know this is the right treatment for me?’ And there wasn’t a right answer for that question.”

Since then, Dr. McGovern has been seeking answers, trying to identify drug targets and associated biomarkers to match the right drug to the right patient. A serendipitous connection early on led to one of his greatest partnerships in this endeavor.

While at Oxford, he and his collaborators defined the differences in genetics for IBD susceptibility that occur between different ancestral populations. This work led to the identification of a gene involved in the pathophysiology of IBD called TNF Superfamily 15. At the same time, Dr. Stephan Targan at Cedars-Sinai had discovered and was studying TL1A — a protein encoded by the gene Dr. McGovern and his collaborators had identified.

The two then found themselves presenting on the same stage at a medical conference. Quickly recognizing a shared pursuit and Dr. McGovern’s complementary expertise, Dr. Targan invited him to join the team at Cedars-Sinai.

Seventeen years later, Dr. McGovern has made a home in California and is now leading the McGovern Lab — also called the Translational Genomics Group (TGG) — at Cedars Sinai. And, after two decades of tireless pursuit, perseverance, and collaboration with Dr. Targan and Dr. Janine Bilsborough, Dr. McGovern’s dream of delivering a personalized approach is gaining momentum with their anti-TL1A investigational therapy.

“Drug development is incredibly hard. We were told that it would be impossible to develop this anti-TL1A drug – that it wouldn’t work, that our companion diagnostic idea was crazy. We couldn’t get industry to take it on.”

Undaunted by the realities of academic drug development, Dr. McGovern and his partners founded Precision IBD, which subsequently became Prometheus Biosciences, and ultimately completed successful Phase 2 trials of their compound. The investigational therapy was acquired by Merck in 2023 and is currently being evaluated in Phase 3 programs.

According to Dr. McGovern, this anti-TL1A compound is completely different from existing therapies and also addresses a critical unmet need – fibrosis in Crohn’s disease. With a unique mechanism of action, it potentially treats both inflammation and fibrosis – and it has a companion diagnostic. If approved, it would be the first personalized medicine for people with IBD.

Grounded in Dr. McGovern’s personal dedication to public service, TGG has taken on many other game-changing projects with an eye toward broad global application. Since the majority of IBD research has focused on European ancestry, Dr. McGovern believes that the most pressing issue for the field is bringing advances to all areas of society.

“Humans are alike,” said Dr. McGovern. “The same fears, worries, hopes. We have so much in common, far more than you might think if you watch the news or look at social media. It is this belief that drives my ethos that we should be trying to solve the disparities that exist in healthcare as opposed to ignoring or exacerbating them.”

One of the lab’s main areas of focus is understanding what molecular signatures underlie the very varied clinical presentation and response to therapy clinicians see with their IBD patients. In trying to understand the complex puzzles IBD presents, Dr. McGovern is embracing opportunities to employ machine learning and artificial intelligence, combining objective data such as radiological imaging and histopathology data with cutting-edge genetic technologies, such as transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics.

“Technology is going to give us some significant help with more advanced analytic approaches. I think that’s the most exciting area for IBD at the moment.”

One example: Dr. McGovern’s lab completed a study that looked at joint inflammation in the spine and hips — symptoms that sometimes accompany IBD. Dr. McGovern credits technology with supercharging researchers’ ability to answer the question, ‘Why?’

“Without machine learning, we would have had to get 1,200 CTs reviewed by a radiologist, one-by-one,” said Dr. McGovern. “Now we can run millions of features of these scans against the 20 million variants in the genome. The ability to look at big data and draw insights today is just exponentially greater than it ever was.”

Dr. McGovern’s team, led by his colleague and mentee Dr. Talin Haritunians, is also working on identifying clinical differences between the sexes in IBD, and how IBD presents differently in men and women. The next iteration of these studies is anticipated in 2025. So far, this research has revealed interesting genetic and immunological differences between the sexes.

“This speaks to the idea of precision medicine,” said Dr. McGovern. “We don’t really think enough about gender when we’re strategizing about what drugs we’re prescribing or developing. It seems like a real missed opportunity.”

Just this year, Dr. McGovern’s career came full circle as he returned to Zambia, just two miles from where he was born, to assemble a consortium to generate genetic data in Sub-Saharan Africa.

“If we’re really going to create new disease classifications and new therapeutics, they need to be available to populations where IBD is really beginning to develop now,” he said. “That’s going to be a big focus of my future going forward.”

Dr. McGovern has led the effort to extend largely European ancestry studies and advances to other populations, including people of African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and East Asian ancestries. For Dr. McGovern, his global focus on spreading advancements is validated every day in his work with patients.

“Every week I see people where our current treatments are failing them. We’ve got no excuse not to work together to change that. People desperately need us to make progress.”

Fortunately, according to Dr. McGovern— having mentored countless professionals who have gone on to lead research and serve IBD patients in the US, Japan, China, Korea, Canada, and now Sub-Saharan Africa — the future is in good hands.

“Really smart, good people are coming through the ranks,” he said. “While you can’t control the future, from a people perspective the future looks incredibly bright.”

Dr. McGovern attributes his optimism, in part, to the passion and perseverance he sees in the next generation — a ‘thick skin’ as he calls it — and the will to pick yourself up after a failure, be resilient, and start the process all over again. He believes these are the keys to success in medicine and science.